Management: Past, Present and…Future?

A C20 Interview with Martin Parker

By Collective 20

[Collective 20 is a group of writers located in different places throughout the globe. Some young, some older; some long-time organizers and writers, others just getting started, but all equally dedicated to offering analysis, vision, and strategy useful for winning a vastly better society than we currently endure. The members of Collective 20 hope their contributions concerning social, political, economic, and environmental issues will generate more useful content and better outreach through a collective publication effort as opposed to individuals doing so on their own. Collective 20’s cumulative work can be found at collective20.org, where you can learn more about the group, see an archive of its publications, and comment on its work.]

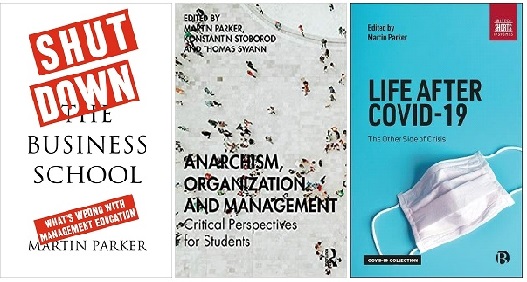

Martin Parker is a Professor at Bristol University (UK) where he leads on the Inclusive Economy Initiative [1]. His areas of study and expertise are organisation and management. He has written many books on these topics, including; Shut Down the Business School: What’s Wrong with Management Education (2018) [2], Anarchism, Organisation and Management: Critical Perspectives for Students (2020) [3] and most recently, Life After COVID-19: The Other Side of Crisis (2020) [4].

C20: There seems to be an interesting overlap between the theme of your latest book and the motivation to form Collective 20. For example, C20 “emerged from the crisis of the Coronavirus lock down to show that, despite feelings of physical isolation and despair, we have much to hope for”, whilst Life After COVID-19 asserts that the pandemic “provides an opportunity to think about what we can improve and how rapidly we can make changes”. This focus on the more optimistic aspects of the situation seems to contrast with the traditional leftwing focus on analysis of what is wrong in the world. Whilst analysis is undoubtedly important do you feel that there needs to be more of an emphasis on vision (what we want) and strategy (how we get there)?

MP: That’s a really great question. And I don’t have a neat answer to it. My sense is, yes, that the left very often paralysis itself with analysis, with debates between various factions that place importance on different theories of capitalism or whatever. And I don’t think we have the luxury or the energy to worry that much about theory, perhaps as much as we have done in the past. My sense is the kind of crises that face us are now so urgent – most obviously the climate crisis but also a whole series of simultaneous social crises as well – that cracking on and doing something is more important really. And, you are absolutely right, the COVID book was written out of that moment – what I think was a very common moment for people on the green-left – when we went into lockdown in March in the UK. The weather was beautiful and I just kept thinking about the possibility of something different emerging from this. The city was quieter, the air smelt cleaner, there were fewer jets tearing overhead, I seemed to be able to hear nature and I was spending more time with my partner, more time cooking, a whole bunch of things that felt quite productive in various ways. And I am not saying that my experience was the same as everyone else’s. For many people it was horror and pain and misery. But the idea of something good emerging from the crisis was really significant for me. And so I collected together a bunch of people to write short essays on various elements of COVID in order to explore how we might change our cities, our money, our ways of thinking about work and home and so on. A whole series of productive ways of reimagining what the future might be.

If I can just amplify a bit, the fetish of theory is something that worries me a bit. This is the idea that theory is like a special place that you have got to get to in order that you can conduct well considered action. That has been the case in a whole variety of different social movements, not all by any means, but particularly on the Marxist left. The idea is that theory is the most prized object of all. And if you can somehow capture the theory, express it, in some multi-volume work with complicated words then you’ve achieved a particular pivot point or something and then action can follow. I just don’t think that that is a very helpful way of thinking about the relationship between theory and practice. There is a unity between those two moments of engaging with the world, and I don’t think we need to get our theory right before we aim action at the future. We need to just try things out, and see if they work.

C20: As highlighted above, your areas of interest are organisation and management. For some people, these might sound like quite abstract and even dry subjects. What attracted you to the study of organisation? Why should other people care about management? How does organisation and management relate to concerns regarding social justice?

MP: Again, really great questions. When I tell people on the left that I work in business and management they normally assume that I am part of the apparatus which appropriates value from the working classes and teaches bosses how to be heartless. I don’t disagree with them that much really. What I am trying to do in a lot of the work I have done is to use concepts like “organisation” and “exchange” in order to think about the importance of considering alternative frames which help us reimagine the ways in which we, as human beings, come together to do stuff, to produce value. So the term ‘organisation’, for example, for me is an incredibly productive one. Management is a form of organisation but it is not by any means the only one. Coops, various forms of worker or community ownership and control, mutualism, local money, and credit unions are forms of organisation too. So it seems to me that the question is really about trying to amplify the imagination we have for different forms of organising in order that we can produce more productive ways of being together on this planet.

That means that some of the knowledge being produced and traded by business schools is actually quite relevant. It’s just that it needs to be turned to very different purposes. So say that you want to create a functioning cooperative, for example, then you need to understand how accountancy and marketing work. You need to understand how to count the cash and the objects that are coming in and the stuff that’s going out and pay your wages and so on. That’s functionally necessary if the place is going to work. Similarly, you need to find a way of reaching customers and selling things and services. Once the revolution has happened we are going to still need to think about these things, they don’t just go away. It is just that those techniques are very often used for, to my mind, fairly distressing social purposes. So, what I kind of want to do is in a sense to socialise the business school in order to ensure that the knowledge that they have is aimed towards socially productive purposes.

C20: Is there a generally agreed upon definition of management within your field? What is your working definition? Historically, when did management – as you define it – first emerge?

MP: The terms “management” is a very contested one. And that is why I very often use the term organisation instead. So what we see is the emergence of the word really around the 17th and 18th centuries in English. It has got Italian roots from mano, the hand, or it is sometimes tracked back to maneggiarre, which is the activity of looking after or training horses. But in terms of its application in the English language you see it sometimes in the theatre, from the 17th century onwards, but much more intensely after the industrial revolution to refer to a particular class of people who were basically overseeing the new factories and offices of the time. So, we are talking about a certain class fraction if you like. The term itself has some quite interesting roots, particularly the idea of managery, a certain kind of skill at organizing. But I think in terms of its contemporary application, I find it very troublesome. Largely because it assumes that what managers do is something that ordinary people can’t do. In other words it assumes insufficiency in most of us. And that is why we need managers to coordinate us. And that is not that often remarked on. In that sense of giving up our autonomy, our control over our everyday lives to a cadre of people called managers, we are also admitting a sort of insufficiency in ourselves, as if we couldn’t do this because we are too stupid to arrange matters ourselves. That seems to me a fundamentally repressive technique of organising.

Nonetheless, I can see all sorts of reasons why, on some occasions, we might concede our authority to various experts. If I’m going to a doctor, it makes sense that I acknowledge that the doctor knows more than I do. And that is, if you like, a freely given acknowledgement of my dependency on their expertise. If someone is going to fix my laptop, I don’t know how to do it so I have to admit that they have knowledge that I don’t. But the term management seems to imply almost a permanent, enduring incompetence on the part of most ordinary human beings and that I find politically very difficult. The term organising, on the other hand, really just suggests that human beings and technologies and nonhumans of various kinds are coming together to arrange our world. And so that seems to me a word that is fundamentally various and plural and suggests that there could be all sorts of ways in which we organize. Not ways that necessarily imply the hierarchy of the managers and the managed. So, for me management is not a useful term. It is quite an oppressive one. The term organising, I think, is potentially a much more productive one.

C20: When did management become professionalised? What is the ideology of managerialism? How pervasive is this ideology today? Why do you oppose managerialism?

MP: From the middle of the 19th century onwards, we can see the beginning of a sort of apparatus that services this new managerial class. The first business schools, for example, were in places like France and Belgium and were associated with the Chamber of Commerce – the emergence of an urban bourgeoisie starting to sponsor different kinds of training, very often accountancy type training initially. You can also see the various ways in which management ‘institutes’ of various kinds are starting to get built – an infrastructure which supports the professional ambitions of this particular occupation. It is not, however, until the last third of the 19th century that it really starts to accelerate. In terms of education, this is the beginning of the American business school, which is probably a much more significant development in many ways. So places like Wharton and Harvard, from the 1870’s onwards, are beginning to organise American business education around a particular set of technologies and forms of expertise, which is the curriculum we largely inherit across the rest of the world now.

At that time there was also a certain kind of moral mission, which quite a lot of commentators (such as Rakesh Khurana and Ellen O’Connor [5]) have written about but has largely been eclipsed now. Early US business schools were clear that they would teach a moral economy that should be guiding the activities of business people. Of course, this isn’t surprising given the huge levels of concentration in American capitalism around that time. This was paralleled by very substantial levels of popular criticism about the impact of big business on ordinary people.

Moving into the twentieth century, business schools grow and start to globalise and the whole infrastructure of management grows into something like a semi-profession. It is not a full profession, in the sense that the medical profession (in most places) is state sanctioned with a very strong professional body that prevents anybody who hasn’t got a particular qualification practising medicine and so on. It’s a semi-profession in the sense that the qualification of the MBA [Master of Business Administration] or some other degree bestowed by a business school, membership of various kinds of professional institutions, attendance at training courses or experience on a CV becomes a way of demonstrating the knowledge that you need to do these kinds of activities. And now we have reached a situation, I think, where many people would assume that in order to be a manager you need to have a certain level of technical competence, you need to use particular forms of language, to understand the mysteries of the spreadsheet or management accounts, and so on.

That is actually very similar to the ways that lots of professions develop anyway. It is a way of locking-up an area of knowledge. There is a famous Marxist sociologist of professions – Terry Johnson [6] – who suggested that the whole idea of a ‘profession’ was a way of claiming a monopoly over a particular labour market, asserting that a particular group have skills and mysteries that other people don’t have. And that effectively allows you to bid up your price because other people can’t compete against you. His two big examples were the legal profession and the medical profession, which persuaded the state to say that nobody else can engage in certain kinds of activities. Management hasn’t achieved that, but I think culturally it has still managed to achieve a certain sort of dominance. If you think now that one in seven students in British higher education are studying some version of management and business. That’s an astonishing achievement! The single most popular subject are variants of management or business, whether accounting, marketing, strategy, operations, finance or whatever. What Johnson is pointing to is the way in which professional authority gets naturalised. We just assume now that doctors have a particular kind of expertise and that it is sanctioned by the state. And the idea of somebody practising medicine without being kitemarked by the British Medical Association, for example, would be something that would be appalling to us. That is an amazing achievement, isn’t it, for an occupational group to say nobody else can compete with us.

C20: Managerialism seems to overlap with some other ideas that have developed over the last forty or fifty years. For example, there is the “professional-managerial class” of John and Barbara Ehrenreich [7] and Michael Albert’s and Robin Hahnel’s notion of the “coordinator class” [8]. Do you think that these ideas are all trying to make sense of the same thing? Or, to your mind, are they different and, in some ways, misguided?

MP: I think, broadly, they are talking about the same kinds of things and effectively what we then have to do to understand this is to have a slightly more sophisticated account of the nature of classes in capitalism. So, a very crude Marxist analysis would basically say you have the bourgeoisie and their functionaries, and then you have the proletariat and there is a simple opposition between those two classes. I think what the rise of the managerial strata does is effectively to make the relay between capital and the proletariat a bit more complicated. Remember that the managerial class is a very large one, as well. We are not always talking about people who have substantial cultural and financial resources themselves, although some of those people may do. A fairly low grade National Health Service manager, for example, is not necessarily somebody who we can put in the same box as a person who is running a FTSE 500 company and yet they are both captured by that general sense of being part of the managerial class.

Let’s assume that we have a ‘class’ that owns capital and shares and land, and then you’ve got a bunch of people who essentially sell their labour – the working classes in the broadest sense. ‘Management’ could be understood as a class in between who are very often representing the interests of the bourgeoisie, of those who own and control, but as we move further down they don’t necessarily share many of those benefits. They are better understood as supervisors, or overseers, to use those Victorian terms, rather than dynamic, strategic chief executives who are always jumping on planes and striding into glass office blocks.

C20: I don’t hear anti-capitalists discussing the ideology of managerialism very much. Do you think it is a blind spot on the left? How serious do you think this blind spot is? The Ehrenreich’s critique of Marxist class analysis shows that the left could become dominated by the professional-managerial class and their ideological interests. In a similar vein, Albert and Hahnel have argued that what is typically referred to as 20th century socialism is better understood as coordinatorism, a system in which “a class of experts / technocrats / managers / conceptual workers monopolise decision-making authority while traditional workers carry out their orders” [9]. What do you make of this analysis?

MP: I think it is a really good analysis. If we take the example of say political parties of the left, from the Soviet Union onwards, or trade unions, for example, what we tend to see is the concentration of a particular cadre of people who make decisions on behalf of other people. Sometimes that might be a really useful thing to do. If you need certain kinds of expertise or you need decisions made rapidly, whatever it might be. It is not always possible to spend a long time consulting. But surely the default assumption should be that the people that you are representing should be as involved in decision-making as they possibly can be. There’s been a sense in which so many left political parties have inherited a certain sort of idea, and this is not unrelated to the question of theory, that only certain people have the intelligence, ability, skill, to make strategic decisions. And then the job of this vanguard becomes to construct the political plan and the rhetoric that will get the masses behind them. That is a really troublesome model, to my mind, and some ways I lean more to anarchist or communitarian accounts of what desirable forms of organising might look like and away from these highly organised party formations, which seem to me very often to have the seeds of betrayal already built into them.

There are a whole bunch of sociologists who have written about this, such as Robert Michels who wrote about the so-called “iron law of oligarchy” in which he suggested very pessimistically that with any group of people – and his example is political parties – what you get is the locking-up of power in a small group [10]. So, if that is the case then we need to work against it. We need to think about ways in which we undo that sort of ideology of managerialism – the idea that a small elite can make decisions on behalf of the rest of us. And that, to me, takes us back to the question of organisation. That is why the concept is so important. Because unless we think about organisation in multiple, various and plural ways we fall back into these old, tired and rather oppressive assumptions about a certain group of people telling other people what their best interests are. In answer to the question, I think managerialism is just as much a problem on the left as it is on the right. The idea that most people are incapable of making decisions for themselves is a really powerful way of keeping people outside the political system and indeed outside meaningful engagement in politics more generally.

C20: You identify the Business School as the main proponent for the ideology of managerialism. You have argued that the Business School should be shut down and replaced by a School for Organising. What do you see as the main difference between these two forms of education?

MP: One of the things that I think business schools do is effectively engage in a particular form of class reproduction by producing people who occupy those managerial roles. So what do the business schools do? They teach capitalism. And they produce the labour power for a particular class fraction. Now, that doesn’t mean – going back to my earlier answer – that problems of organising our world simply go away if you get rid of business schools. The problem of organisation is still there. So I do think we need ways of collectively getting together to talk about how we organise. That, if you like, is the most complicated problem human beings face. If you look across history and across geography you see that humans have lots of different ways of arranging themselves, of thinking about their possibilities, the methods they use to exchange or own things, the way they occupy positions of power or distribute status and so on. Human beings have solved these problems in lots and lots of different ways. But what the business schools do is suggest that there is only one best way – that it’s managerialism. So if we want a much more experimental approach to organising – one that takes our values much more seriously in terms of idea about that much misused word ‘democracy’ as well as sustainability, equity, inclusion or whatever – then we are going to need to have ways of talking about the variety of organising that exists.

The analogy I’m almost always falling back on now is that if you were studying plants, trees, flowers, fungi and so on you would assume that there was a huge variety of ways in which this particular group of living creatures solves the problems that face them. They don’t only have one strategy. It seems to me that human beings need to develop that capacity as well. Rather than assuming that organining is something that has to be done to them by a particular cadre of people, to instead creatively think about all the different ways in which we can come together and do stuff. And that is what the School for Organising would teach, I think. And it is predicated, for me, very much on the idea that we are all organising creatures – that there is not some sort of exclusion that means that I can organise but you can’t. We all do it. The practical question is how we come together and do it in complicated ways that generate collective value – both economic and social.

C20: I’d like to finish by asking you about the future of management. In their vision for a participatory economy, Albert and Hahnel propose self-management – “give people a say that is roughly proportionate to the degree they are affected” – as an appropriate form of decision-making [11]. However, they also argue that, for self-management to function, the current division of labour – which distributes empowering tasks out unevenly (technically known as the “corporate division of labour” – must be dismantled and replaced by a division of labour that distributes empowering tasks out more evenly (what they call “balanced job complexes” [12]). What do you think of self-management? Do you agree that we also need to rethink the division of labour, the way tasks are distributed, the way jobs are designed? What implications, if any, do such insights have on your idea of a School for Organising?

MP: To start off, the fact that Albert and Hahnel use the term ‘self-management’ is not for me a problem.There is a long history of people who have talked about self-management in the general sense of cooperative enterprise and mutualism. I don’t think they are using the word management in the same way that I am. I would rather they talked about self-organisation, or something, because then it doesn’t have all of those historical sediments of the ideas of managers. But nonetheless, I am very positive about the kind of participatory economy that they are putting forward. That is one in which ownership and control is much more effectively distributed than it is at present. And they have got some quite complicated ways of thinking about how individuals might participate, and communities can be involved and so on.

Questions concerning the division of labour are relevant too. Because if we are going to think about designing a new economy then we are going to need some people who really are specialists. A doctor is going to be a really useful person so we probably want to be investing in training people in medicine. Or people who know how to mend shoes. Or people who know how to grow particular kinds of crops. We are going to need expertise. The question is, how that expertise is rewarded? Do we assume that knowing about kidneys is inherently more difficult and superior than mending shoes or growing crops? It seems to me that that is not necessarily the case. This goes back to our earlier discussion about the way that professional bodies have locked-up particular bodies of knowledge. So I think that it is really important to acknowledge that we are going to have a division of labour. But the social implications of that division of labour, for me, are rather open. They don’t necessarily mean that the person who, let’s say coordinating a particular activity, should have higher power and status than the people who carry it out. There is a beautiful analogy by the anarchist art critic Herbert Read, who uses the analogy of the railways [13]. When we are talking about the railway we don’t assume that the signal box is more important than the track. Or that the station is more important than the bridge. It is part of a system. And each part of that system needs to function effectively, not that one should be rewarded more than another. So, it seems to me that is the kind of principle that we need to apply to a participatory economy. Yes, we are going to need a division of labour but we need to think very hard about making sure that the social consequences of that do not become dysfunctional.

C20: Thanks again, Martin! Are there any closing statements or comments that you would like to make before we finish?

MP: Just one, I guess. To go back to the start, I can imagine many people on what I broadly call the green-left being really surprised by the emphasis that I am placing on the business school. But it seems to me that, in terms of any account of the sort of rapid social change that we need, the power of business school education needs to be understood. At the moment there are something like thirteen thousand business schools globally. And most of them teach conventional forms of capitalism. Trying to capture and reorient those forms of education seems to me a really valuable and important thing to do. And as I have said, the problems the business school grapples with do not go away once you get rid of capitalism. They are still going to be there. We still need to think about how we coordinate our activities and so on. So in a way I want the long march through the institutions, from my point of view, to begin with the business schools. They seem to be really important places for articulating the possibilities of what a new politics and new economy might look like.

[INITIAL SUBMISSION: Mark Evans | AUTHOR: Collective 20 (Andrej Grubacic, Brett Wilkins, Bridget Meehan, Cynthia Peters, Don Rojas, Emily Jones, Justin Podur, Mark Evans, Medea Benjamin, Michael Albert, Noam Chomsky, Oscar Chacon, Peter Bohmer, Savvina Chowdhury, Vincent Emanuele)]

Notes

- For more information on the Bristol Inclusive Economy Initiative: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/temple-quarter-campus/research-teaching-and-partnerships/inclusive-economy-initiative/

- For more information on Shut Down the Business School: http://www.plutobooks.com/9781786802408/shut-down-the-business-school/

- For more information on Anarchism, Organisation and Management: https://www.routledge.com/Anarchism-Organization-and-Management-Critical-Perspectives-for-Students/Parker-Stoborod-Swann/p/book/9781138044111

- For more information on Life After COVID-19: https://bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/life-after-covid-19

- Khurana, R. (2007) From Higher Aims to Hired Hands. The Social Transformation of American Business Schools and the Unfulfilled Promise of Management as a Profession. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; O’Connor, E. (2012) Creating New Knowledge in Management, Appropriating the Field’s Lost Foundations. Stanford, CA: Stanford.

- T Johnson (1972) Professions and Power. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- See the lead article in Between Labor and Capital, edited by Pat Walker, published by South End Press.

- Albert and Hahnel define the coordinator class as, “Planners, administrators, technocrats, and other conceptual workers who monopolise the information and decision-making authority necessary to determine economic outcomes. An intermittent class in capitalism; the ruling class in coordinator economies such as the [former] Soviety Union, China, and Yugoslavia”.

- This definition is taken from the Glossary of Looking forward: Participatory Economics for the Twenty First Century, available here: https://zcomm.org/looking-forward/

- R Michels (1912/1962) Political Parties. New York: Free Press.

- For an example of the thinking that argues for this form of decision-making and specific definition of self management, see Chapter One of Occupy Vision: https://zcomm.org/znetarticle/chapter-one-of-occupy-vision-by-michael-albert/

- Albert and Hahnel highlight the fact that all economies have some kind of job complex and define Balanced Job Complexes as, “A collection of tasks within a workplace that is comparable in its burdens and benefits and in its impact on the worker’s ability to participate in decision making to all other job complexes in the workplace. Workers have a responsibility for a job complex in their main workplace, and often for additional tasks outside to balance their overall work responsibilities with those of other workers in society”.

- Read, H. (1963/2002) ‘The cult of leadership’. In idem, To Hell with Culture, and Other Essays on Art and Society. London: Routledge, pp. 48–69.

Leave a Reply